Until the age of eight, my life was experienced within the confines of a one-bedroom apartment. When my brother came along, we left the city for the suburbs. Going from urban to suburban living changed my world overnight. Until our move, it was just my parents, my grandparents who lived upstairs and a couple of kids who lived in our apartment building. Suddenly I found myself in a strange new land, one I was ill prepared for.

The resiliency of a child is a necessity for survival and being bereft of self-confidence and coping skills, I was thrown into the deep end of the pool. We moved into a neighborhood where there were dozens of kids, most around the same age and all much more acclimated to the ways of the hardscrabble streets of suburban America in the early 1960’s. I adjusted and eventually found my way making a few friends but like me, they occupied the lower rungs of the neighborhood hierarchy. My parents rarely drove me anywhere, so I either walked or bicycled. On Saturday’s, I walked the goyim gauntlet through the neighborhood to Hebrew School to the chants of Christ killer and Jew-boy.

I had my own small group of tormentors, however, a few houses down lived an older kid who chose not to join the cliques, instead arbitrarily moving in and out of daily neighborhood life. He had a way of remaining in the background when he chose but would take charge of things when the mood suited him. Andy was about five years older and unlike all the other kids, marched to the beat of his own drummer. My first memory of Andy was a bunch of us playing in the brook beneath an old white wooden bridge. One hot summer day we decided to head to the brook to do the kind of things that kids left to their own devices did in the early 1960’s. At the deep end of the brook as we all prepared to jump in, Andy suggested that we all skinny dip. We all looked at each other and collectively rejected the idea. Andy stripped naked and jumped in just the same.

Andy was five years older than most of us and so it made sense that as we grew older, he would assume a more prominent role in our little neighborhood eco-system. Many of the parents wanted us to stay clear of him. The sense of excitement and adventure that drew a bunch of young kids to Andy was experienced as a vague sense of fear and trepidation by the parents. This was decades before ‘helicopter parents’ and ultimately as long as we returned home alive before dark, our parents felt they were doing their jobs.

Andy lived with his parents and sisters. His dad was an imposing figure that seemed to come and go at all hours of the day and night. Andy’s father invoked a primal fear both in the adults and the children of the neighborhood. He would frequently leave the house in the evening when all the other fathers were arriving home from work. At the time I thought little of it. Several years later when Andy started driving, he took us for a ride to this house in a nearby town with a long winding driveway that had ceramic statues of heads on top of the wall as one navigated the circuitous route towards the large house. It was rumored that this was the home of Richey “the Boot” Boiardo head of one of the largest crime families in New Jersey.

Legend was that the statues were of mob guys that Richie allegedly had ‘whacked’ and then disposed of somewhere on his property. The more we all screamed for Andy to turn the car around, the greater the glee spread across his face. Later we all wondered if this is where Andy’s dad spent his nights at.

But Andy’s exploits had begun long before that day. In 1962 during the Cuban missile crisis, on a summer night when we were camping out, Andy told us that the Russians had just fired a missile bound for New York City and we all should go home and say good-bye to our parents and return to our camp to patrol the neighborhood. We believed Andy and that night we all climbed trees with baseball bats just in case the Russians found their way to northern New Jersey.

A few years later Andy and I camped out in my friend Glenn’s back yard. During the night Glenn and I decided to roam the neighborhood shining our flashlights in people’s bedroom windows. When we returned, Andy told us that an elderly woman whose bedroom window we shone our flashlight in had a heart attack and died. It never occurred to us just how Andy knew this but we both bought it, hook, line, and sinker. As Glenn and I stayed up all night, both bordering on hysteria, Andy just sat back and enjoyed the show. It was only in the early morning hours when Glenn and I decided to run away from home, that Andy let us in on the joke.

Andy was equal opportunity tormenter, and I was just part of the stage set. His antics were more like productions designed to extract the maximum amount of outrage and shock. Once he had his sister lay on their living room floor, pretending to be dead. Leading us into the darkened living room, he screamed, “she’s dead”, then laughing hysterically to our collective screams. Despite these antics, there were times where Andy would become my protector and defender. Looking back, I like to think that he recognized my pain because beneath the theatre, dramatics, and bravado, he was dealing with his own pain and conflict.

Andy last automobile escapade was the most serious and dangerous. With five of us packed in his car, Andy decided to throw his chips as well as ours to the center of the table. On a 35-mile per hour street that ended at a busy four-lane highway, Andy gunned it down the road and blindly crossed four lanes of traffic and onto a dirt road across from the highway. Sheer dumb luck is the only thing that saved us.

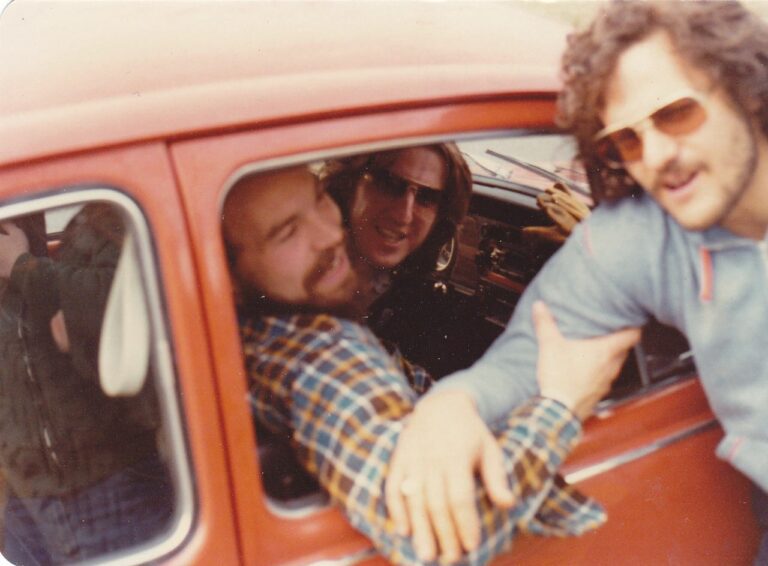

The years went by and Andy mellowed but that outrageous kid from our childhood would every now and then emerge. One weekend a few of us drove to see a high school friend play basketball on scholarship at a college in West Virginia. Andy was attending a different college about 20 miles away and he met us to see the game and catch up. Sometime, after the game, we ended up at a local bar, when we noticed that Andy was no longer with us. With not as much as a good-bye, Andy just slipped away. Back in the old neighborhood during college breaks and the summers, Andy would disappear and then just as suddenly show-up. He dropped out of college and ended up working at the Post Office.

As the 1980’s rolled around, Andy left the relative safety and confines of our town. One day, he returned to the old neighborhood and while I did not know it at the time, this was going to be Andy’s last thrill ride down the highway of our cloistered suburban town. Andrew as he was now known, and his ‘friend’ both outrageously and garishly dressed were shocking but like almost everything he did, this was done by design. As Andrew’s escapades as a young boy were meant to illicit shock and outrage, so was this visit. The afternoon was spent regaling us with their exploits. Andrew seemed especially proud of his late-night forays to the meat packing district on the lower west side of Manhattan, entering dark empty trucks and having anonymous sex with strangers.

A few years later, I ran into an old neighborhood friend who saw Andy at Penn Station. Sadly, he recounted seeing a ghost of a man who I always viewed as larger than life. Gaunt, feeble, his once handsome face dotted with lesions, he recounted how AIDs, the scourge of the 1980’s had visited upon our old neighborhood friend. Soon after, we learned Andrew had passed away and it was not long after that my old backyard camping buddy Glenn died of a drug overdose.

At his core, Andy was the same person as an adult as he was as a young boy. Beneath the outrageousness that he tried to project to the heterosexual Leave it to Beaver existence of 1960’s suburbia, his crazy antics were really an attempt to cope and fit in.

Waiting out the COVID-19 pandemic in the safety of my home, I find myself reflecting on loss and returning to those dark days of the 1980’s. But mostly, I still mourn the loss of a unique human being taken way too early.